前言(略)

填空法创于我国,估计在唐代或更早时期它已是我国围棋计算胜负的主要方法。这里冠以“唐宋”二字,并非认为它的上限不出唐代(汉桓潭《新论》中已有“世有围棋之戏,……及为之,上者……成多得道之胜”的记载,这里的“道”就指棋盘上的空点,可见从汉到唐、宋,人们对围棋胜负依据的认识是一致的),而是为了与流行于日本及欧美等国的填空法所区别。

The so called Filling Scheme is originated in China. It is estimated that by the Tang Dynasty it had already become the most popular way to decide the game result. We hereby name it with Tang Song doesn't mean that we believe it had come into being no later than the Tang Dynasty. We just want to differentiate it with the Filling Scheme that is popular in Japan and Korea nowadays.[1]

唐宋时期距今千年,围棋资料极其有限,因此给我们留下了许多困惑不解的谜。对于这种填空法,尽管我们竭尽所能地进行探索,甚至加以主观推理,也仅能“雾里观花”,知其大略。然而,它却是实实在在曾长期流行于中国棋界的……

It has been over a thousand years since Tang and Song, and the documents for go survived today is so limited. Therefore it left us so many unsolved puzzles. We have been studying this Filling Scheme for very long time, and sometimes we even made very bold guesses, however we can only gather a rough idea about its logic. Ironically this rule had been governing Chinese go games for so long a time.填空法人称“以空为地”,唐宋填空法也不例外,但它的“地域观”与今人并不完全一致,我们试举宋本《忘忧清乐集》中所载“金花椀图”为例。

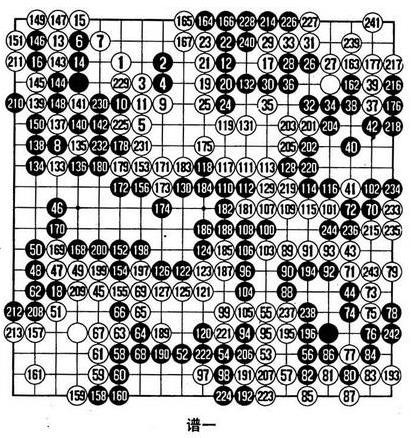

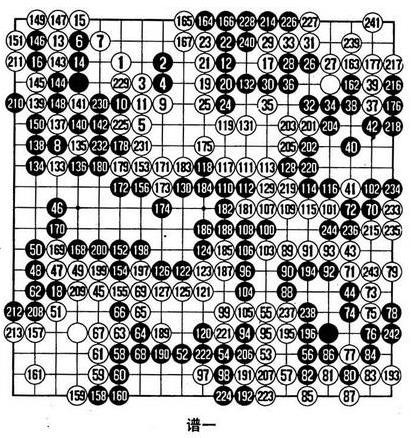

Filling Scheme was known as taking the unoccupied points as area. And the Tang/Song Scheme is no exception. However there's some differences between this rule and what we thought. Let take 金花椀图, a game documented in 《忘忧清乐集》, as an example.谱一“金花椀图”全谱(其SGF格式的棋谱),谱侧注明:“……阎景实白先;顾师言黑胜一路。各一百二十二着。黑杀白六子,有四十路;白杀黑六子,白有三十九路。”

The comment besides the game record reads " 阎景实 plays white; 顾师言 plays black and win by one route. They both made 122 moves, black captured 6 white stones and had 40 routes; white captured 6 black stones and had 39 routes."以上记载说明本局计算胜负的程序是:终局以后,双方先各自将对方的死棋(包括已被提取的死棋及盘面上的死棋;全部填入对方所围的空点中,然后采用差额计算法比较双方在盘面上拥有的空点,胜负之数。其手续先后与流行于日本的填空法一致。这里中国的“胜一路”与日本的“一目胜”等同(“目”也是中国古代盘上空点的称谓如汉桓谭《新论》述及围棋时即有“趋作罫目”之说),由此也可窥中、日两国计算法之间的渊源关系。

This comment tells us: when the game is over, the players should put the captured stones (both already removed from the board and those still sits on the board but deemed dead) into their own area, and compute the difference of the routes that has been occupied. This practice is identical to the Japanese rule. Here the Chinese word "win by one route" is the same as the Japanese description "win by one moku". [2]谱一金花椀图

可是,倘若我们进一步研读棋谱和注文,就会发现唐宋填空法的独特之处了。

But if we further study the game record and the comment, we can find some differences.首先,棋谱注明“各一百二十二着”,这与明清以后包括日本在内的棋谱着手纪录均不相同。值得注意的是:谱中黑244亦即最后一着棋分明无路(目),但还是要走,以凑成“各若干着”偶数终局(宋本《忘忧清乐集》中收录唐宋完整棋谱四局,均以偶数终局,与本局相仿,可见不是某种巧合,否则就不必注明“各若干着”了,不同于“无目官子”完全不收的日本填空法)。唐宋人为什么如此强调双方着手平衡?初看之下,似乎他们将双方一人一着理解为实战中不可分割的“一个回合”。

First, it explicitly stated that "both made 122 moves". This is different from the game records in Ming/Qing Dynasty and the Japanese records. Furthermore, notice the last move, black's 244 doesn't have any value, but it is mandatory. That's because that move helps to balance number of moves, therefore we can read the template words "they both made how many moves". 《忘忧清乐集》, a book written and published in the Song Dynasty, has documented four games in full completeness, and all have even moves and the statement "both made XXX moves", just like this game. So this is not a coincidence. Now if we compare it with the Japanese rule, which don't require the player to make valueless moves, we will naturally come to a question: why Tang/Song rules emphasize the balance of the number of moves? It looks like the rule deems a round as a indivisible unit.不过,如果我们作进一步推理,就会感到:对填空法来说,偶数终局可能有更深一层的用意。

With further thinking we can find there's some other reasons behind this requirement.

围棋对局,双方一人一着,看似平凡,却寓有容易被忽视的“理”试问以上棋谱,为什么弈至244着宣告终局?原因无非是双方承认局面上已无路可争,于是可以采用简化与省略的办法——即筛汰不必要的着法以算出胜负之数。可是,如果官子结束棋局仍未澄清(存有死活不明或有争议的棋形)。那末,实战解决终究难以避免。而这种地域范围内的实战只能遵循一人一着的原则进行,任何一方不得少下一子以回避自填路(目)数。因此也唯有偶数地进行,才体现出双方互不吃亏。

编者注:总结如下,一人一手,不得放弃,允许虚手(直接交俘子一枚给对方),偶数终局。

这里,笔者试举“盘角曲四”为例来加以说明。

Now let's take Bent Four in the corner as an example.《敦煌棋经》称"角旁曲四,局竟乃亡",《棋经十三篇》称"角盘曲四,局终乃亡”。可见"盘角曲四"被判为死棋,由来已久(请注意局竟(终)二字,这个盘角曲四是孤立无援的,如果终局之前出现"双劫"或“公活”(对有盘角曲四棋块一方有利的公活)等,就又当别论了。

In 《敦煌棋经》, it says, "角旁曲四,局竟乃亡", which means, "Bent Four in the corner will be killed when the game finishes.". So we can see that Bent Four in the corner is sentenced to be dead since very long ago. But notice the word finish. This implies the group is helpless. If there were favorable seki or double ko exists, things will be totally different.图一 十一道棋盘,左上黑呈“盘角曲四”,死灰不能复燃了,理由何在?

In picture one(图一), the upper left corner is a "Bent Four", and it IS dead. Why?

不少棋界人士认为:填空法(指现行日本的)存在明显欠缺,那就是在地域中补劫材要自损目数。例如左上黑角虽说死定,而事实上白方必须在A、B、C 补劫材,然后再在D、E紧气,最后才能动手置黑棋于死地,但白A–D既然着着损目,又怎么能硬性规定盘角曲四无条件死呢?这就使人困惑了。

A lot of Go players believes the Japanese's Filing Scheme has an obvious drawback: you have to fill your own area to get rid of the ko threats. For example, although the upper left corner is dead, it's not captured yet. In order to capture it, white must reinforce at A, B, C, and then kill the liberty at D,E, and afterwards he can start to execute. But if all those moves are necessary and can help to reduce white's area how can the rule say Bent Four in the corner is dead?不过,如按唐宋填空法--双方着手平衡,不绝对排斥“无路官子”不收,图中现象就容易理解了。

If we follow Tang/Song scheme, things will be easy. Tang/Song's rule is indifferent about occupying neutral route.图二 双方将带“圈”记号的无路官子补上后(就填空法而言,这几着棋无关地域的增减,与图中白1以下与地域增减有关的着法不同),然后白1补劫,黑2为保持着手平衡,亦要在地中相应地自填,以下双方进行至12 ……

(pic 2). Both the players take the neutral points first(this has no impact on the result of the game), and white begin to amending for ko threat. And as an obligation, black should also make move in his own area.

图三 前图的继续,白5提后,黑6为保持着手平衡,不得不走,结果盘角曲四被歼,胜负之数并无增减。

(pic 3), As an obligation, when white play 5 and capture the black stones, black should also make 6. And the result of the game remains the same.

看来,填空法判盘角曲四为死棋,也是一种简化与省略,而且与着手平衡是配合的。

In this view, to deem Bent Four in the corner as dead is just a simplified practice, and it is related to the balance of the number of moves.因此笔者臆测偶数终局,很可能是填空法处于初级阶段(即尚未找到简化、省略着法途径时)的一种规定,而到了唐宋时期,尽管在多数情况下以丧失意义,但仍作为双方公允合理的象征而保留着。

(

注:赵之云先生关于偶数终局的观点从这里开始向后退了,我个人认为无论何时,也不能低估偶数终局的意义。) With this analysis, I guess "the requirement to have even moves to finish the game", is just a vestige from the early time of the Filling Scheme, (because they had not found a simpler way that can skip more moves and decide the game result much earlier ). At the time of Tang and Song, although it is not really needed, it is still kept as a sign of fairness. [4]至于

"无路官子"唐宋人不是绝对摈除不占的,推理下来,有两种情况可能要占”无路官子",其一是后走一方为保持手数平衡,这一点己有棋谱证明;其二是当局中出现疑难或死活不清的棋形时,应填满"无路官子"然后实战解决,这一点从唐宋人判"盘角曲四"无条件死"中隐约可见。另外,棋谱注明。黑有四十路,自有三十九路

"。但如按日本填空法--活棋围有的空位即是地来计算,则黑有四十六目(路),白有四十五目(路),与唐宋填空法相比黑白双方各有六目(路)之差。为什么会有如此明显的差额呢

?棋谱资料如实地加以反映

:盘上黑白双方各有三块活棋如果按双方'各若干着"一人一着的规律继续进行下去,结果每块活棋(不包括公活)不论围空多少,总有两点任其空虚,这种空点就因己方棋子不能再填、对方也不得入子而不算"路"。以下,笔者试用七路小棋盘进行推理,请看唐宋人对围棋决定胜负的。

”路"是怎样理解的。图四

假设进行至30着,全局结束。图五

将白方死子与黑方死子相互填入对方围有的空点中,呈图中形状,然后计算胜负。

图六

这是示意图,双方如继续进行,黑方填完1至6着后,己不能再行自填,否则将影响黑惧的生死;而白方除了可填1至6着保持双方着手平衡外,还多余A位三点,白共有9点可填。

所以,如按唐宋时期棋谱纪录应这样注明

:"......

各15着。白胜3路。黑杀白1子,黑有6路;白杀黑4子,白有9路。"由此可知,在唐宋人观念中,凡棋赖以生存的起码空位都不是

"路"。换句话说,凡“路”都必须己方的棋可去占领。应该承认,唐宋人对地的见解虽与今人相殊,但自成体系,言之成理。一块活棋,不等于就是拥有地域的棋,正如一个仅有口气的活人,不等于就是有产者一样。此外,如

"三劫循环”"四劫循环”"长生劫"等珍奇棋形,唐宋时人又是怎样处理的呢?唐宋人的处理方法,与日本规定的

"无胜负"大致相同。《棋经十三篇》交代得很清楚,"有无休之势,有交通之图",作为循环往复无法终局处理。《忘忧清乐集》中有”长生八俊势"以"五劫循环"无法终局,即是明证。| [1] | According to 《新论》, which was written by 桓潭 of the Han Dynasty, "Go is a game that who can occupy more routes wins". With the understanding that route mean the available crossing on the board, we can conclude that in the Han, Tang and Song Dynasty, the way to decide go game result was consistent. |

| [2] | Actually in China, "目" which is pronounced as "mu" in Chinese and "moku" in Japanese, was also used to refer to the unoccupied crossing on the board. For example in 桓潭's《新论》, when he talked about Go, he said "趋作罫目". This is also an evidence that the Japanese rule is orignited from the Chinese rule. |

| [3] | Chinese editor's comment. Play in turn, can not relinquish. Virtual move, which means hand back a captured stone to your opponent, is allowed. |

| [4] | Chinese Editor's comment (also the translator's opinion) Mr. Zhao retreats here. I don't agree with him in this point. I believe the importance of the principle of "even moves to end the game" can not be over-estimated. |

还有,唐宋填空法是如何处理“公活”棋形地域的?对此尽管还没棋谱资料验证,但我们只要懂得唐宋人的地域观,再注意到唐宋与明清之间在计算法方面有同出一源的关系,那么,我们对此也可试作探索了。

图七黑▲两子与白方两块棋构成公活,试问如按唐宋填空法,将怎样判断其中地域?

图八白方可在左边A位及右边B位自填不影响白棋的生存。故日左、右两块各有一路,计二路,黑棋无路。

如此处理公活,显然比日本填空法硬性规定‘公活无目”合理,否则,此后黑棋如在A或B位投入当劫材,为什么又成了自损目数之举?这就很难自圆其说了。

图九这是50年代一位美国棋艺研究家对日本填空法提出的质疑图,就棋形来看,如果“公活无目”,那真要为白方叫屈!再说,黑方如在A位扑寻劫,又将怎样解释?

┌○┬○┬○A┬○┬○┬○●┬┬┬┬┐

○●○○○●○○●○○○○●┼┼┼┼┤

├●○●●●●●●●●●●●┼┼┼┼┤

●●●○┼┼┼┼┼╋┼┼┼┼┼╋┼┼┤

├●○○┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

●●○┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

○○○┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

├┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

图十如按唐宋人的地域观,白方可占领A位六点,不影响棋的生存,故白有六路;黑方无点可填,黑无路。

A○A○A○AA○A○┬○●┬┬┬┬┐

○●○○○●○○●○○○○●┼┼┼┼┤

├●○●●●●●●●●●●●┼┼┼┼┤

●●●○┼┼┼┼┼╋┼┼┼┼┼╋┼┼┤

├●○○┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

●●○┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

○○○┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

├┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┼┤

以上两例对公活路数的判断,虽然还缺乏棋谱资料验证,但与唐宋人对地域的见解相符,后来明清人在处理公活时与此也保持一致。所以就计算法而言,怎样对待“棋赖以生存的起码空位”正是中国古棋(由唐代或更早直至清末)与日本及受日本影响的棋的重要区别。写到这里,笔者试就唐宋填空法作个小结。

如果我们不因为唐宋填空法不合现代潮流而存有先入之见的话,应该承认:这已是达到相当高度的计算法,具有简洁、合理、自成体系等优点。

唐宋人的地域观是不含糊的。所以如“公活无目”等硬性规定恐怕多半是日本“土产”,与唐宋填空法无涉。

唐宋对局不绝对排斥无路官子不收,仅此一点就具有灵活性,如终局时盘上存有“宽气劫”、“紧气劫”等少见棋形,或许也能找到比较妥善的解决方案了。

又有些棋界行家认为:日本取消了“还块子”。(实际上是取消了“活棋的起码空位不算地。)是日本对围棋的“改革”与“贡献。其实,中、日双方对“地”的认识仅能说是各有各的理由。取消“还块子”对围棋变化的丰富与否亦无多大关系。当然,中、日两种填空法的差异是明摆着的。所以到底是日方改进了中国的填空法?抑是日方对中国的填空法向来不求甚解?这一切至今还是个谜。

总之,笔者并不想对这一早已消逝的、令人迷离惝恍的计算法作过分的宣扬(它的消逝当然也是新陈代谢、优胜劣败的结果)。不过,本着实事求是的精神——中国古人创造的填空法自有所长,作为后人的我们,对此应给予合情合理的评价。

续